Published in JNS.

On the third anniversary of his mother’s death, a friend shared the story of her life during the Holocaust. He told us about how she escaped before the Ukrainians and Nazis came for her family, and was saved by a family of righteous gentiles. Next, she hid in the forest with partisan fighters, contracted typhoid fever and was found by an uncle she stayed with in the woods until the war ended. As her son told her story, he said that she always smiled and was pleasant, but no one knew the demons she was suppressing.

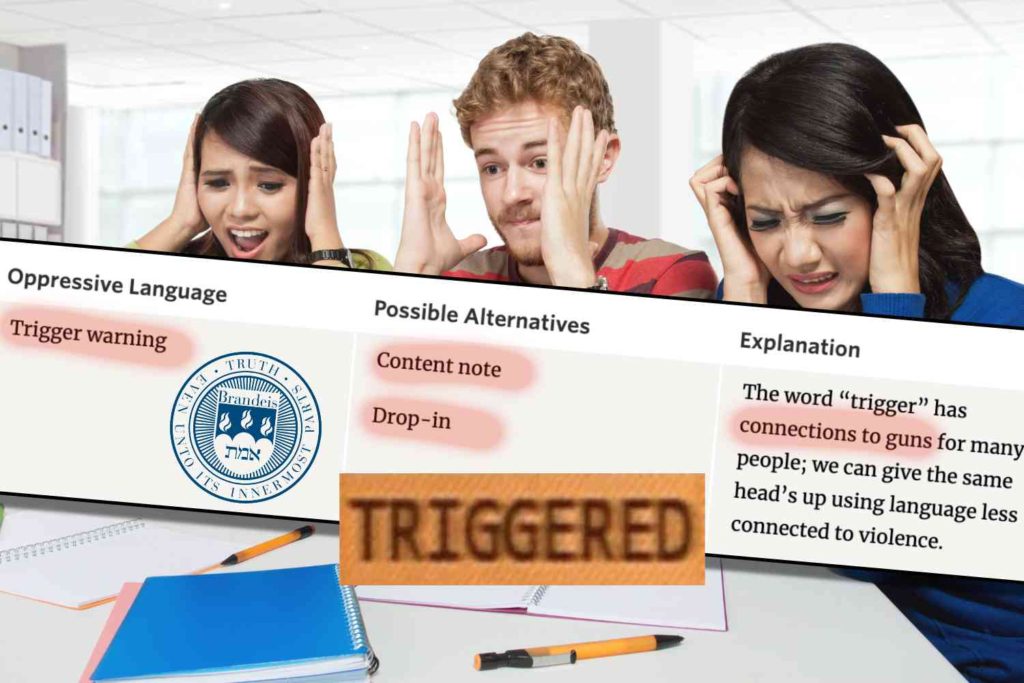

As I listened to her story of how she survived the Shoah, I thought of today’s college students and what they claim traumatizes them. I am referring to images, ideas and discussions on topics that are not considered politically correct. Students have been taught to believe that they are triggers for emotional distress, to be carefully avoided.

I think it’s fair game today to contrast real calamities and the psychological trauma they produce with what today’s students describe as traumatization. Suppressing, warning, punishing and canceling triggering content does a disservice to students, trivializes real trauma and is an assault on our Constitution’s First Amendment.

Triggering is not a rare phenomenon. According to an NPR survey, nearly two out of three college professors use trigger warnings whether their students request them or not, in effect editorializing educational material. For the progressive, intersectional crowd, triggers can be either a conscious or unconscious message that ignites what our young people describe as an overwhelming feeling of discomfort that invades their safe spaces.

A trigger can be completely innocent, a micro-aggression. A professor or student might be unaware that their words could offend; still, it is considered a form of violence to contemporary academia and student bodies. For example, saying the word “Zionist” may trigger psychological distress to those who view Israel as a genocidal regime of baby killers. The response to those infractions is more akin to censorship, to a lack of respect for differing views.

Let’s differentiate between legitimate trigger points and what students complain about. A genuine trigger would be something that would elicit a flashback for someone who has experienced Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder or is suffering from mental-health issues. Real triggers “might cause an extreme and unconscious reaction for people who have experienced trauma, physical or sexual assault, combat or natural disasters.” This is not what we are speaking about.

The University of Chicago in 2016 swam upstream against the politically correct current and wrote a letter to incoming students about trigger warnings. “Our commitment to academic freedom means that we do not support so-called ‘trigger warnings,’… we do not condone the creation of intellectual ‘safe spaces’ where individuals can retreat from ideas and perspectives at odds with their own.”

What is the danger of triggers?

Alan Levinovitz, an assistant professor at James Madison University, wrote in The Atlantic that students’ “ability to speak freely in the classroom is currently endangered. … Whatever their original purpose … trigger warnings are now used to mark discussions of racism, sexism and U.S. imperialism. The logic of this more expansive use is straightforward: Any threat to one’s core identity, especially if that identity is marginalized, is a potential trigger that creates an unsafe space.”

Students, professors and workers of all stripes now self-censure to avoid being accused of micro-aggressions or worse. Loss of friends, being bullied on social media or having lost career advancement opportunities are well-known consequences for those who speak their minds and go against approved speech. Jewish students are especially vulnerable with many not only avoiding talking about Israel but hiding their Judaism for fear of being intimidated by the anti-Israel crowd.

A 2021 Brandeis Center for Human Rights survey revealed that nearly two out of three Jewish students on campus who identify positively with Judaism feel unsafe and half hide their “religious identity to avoid physical or verbal attacks.”

Title VI prohibits discrimination based on race, color or national origin in any program that receives federal funds. Universities receive federal funding. In 2018, the U.S. Department of Education Office of Civil Rights began to use the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition of anti-Semitism when examining questions of anti-Semitism on college campuses under Title VI. The executive order that allowed Jewish students to receive the same protection under Title VI as other groups are still in effect but have not been activated for use by the new administration.

We need the Biden administration’s education and justice departments to step up and defend the rights of Jewish students, as well as protect the civil rights for the diversity of thought on college campuses. The more frightening question to ask is why in 2021 should American Jews need any protection at all?