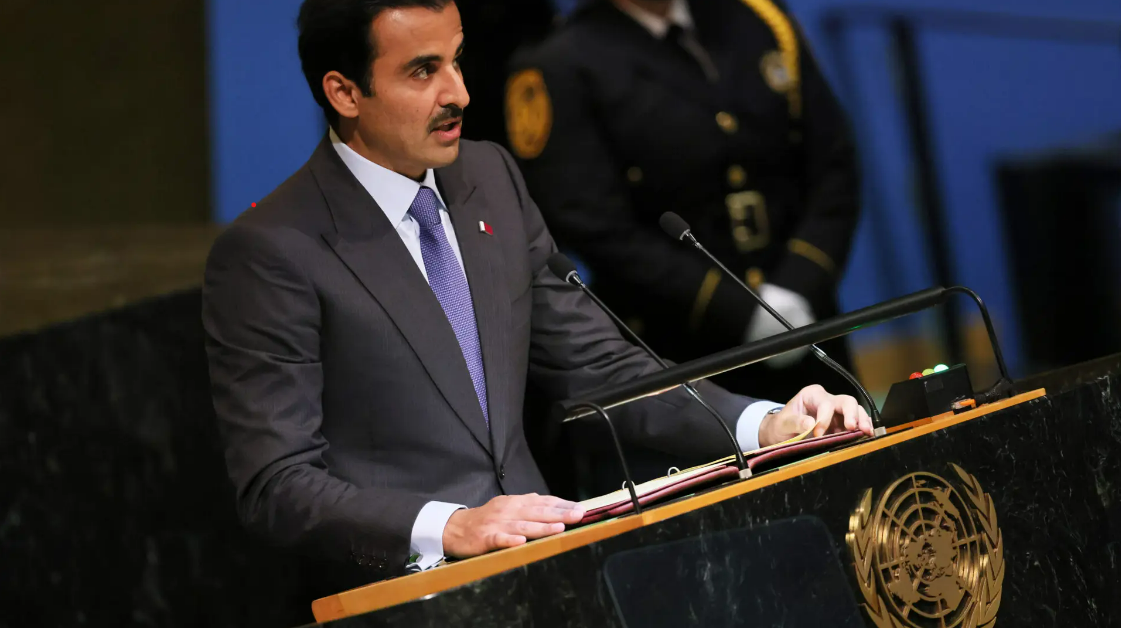

Photo: Qatar’s Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al-Thani speaks at the 77th session of the United Nations General Assembly at the U.N. headquarters in New York on Sept. 20, 2022. Michael M. Santiago/Getty Images.

Published in the June 2, 2023 by The Messenger.

On a recent visit to Doha, where I spoke with Qatari and American foreign policy officials, I was reminded of the question that always arises when talking about U.S.-Qatar relations: Friend, foe, or a little of both?

In January 2022, President Biden designated Qatar a major non-NATO ally, a designation the State Department calls “a powerful symbol of the close relationship the United States shares with those countries and [one that] demonstrates our deep respect for the friendship for the countries to which it is extended.” At the time, the Department of Defense reported that Biden and Qatari Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani “discussed shared regional security interests, including de-escalating tensions in the region, countering terrorism, and the threats represented by Iran.”

Yet, in 2019, the Center for Security Policy claimed that when the Qatari emir met with former President Donald Trump, Al Thani was not truly a U.S. friend, despite “the smiles, handshakes and multibillion-dollar deal-signing.” Although Qatar hosts an important U.S. military base, the Center claimed, it “remains a state sponsor of global jihadist subversion, extremism and terrorism” and has been “growing closer” to Iran. And, in 2014, a New Republic headline read: “Qatar Is a U.S. Ally. They Also Knowingly Abet Terrorism. What’s Going On?”

During my meetings with Qatari and U.S. officials, however, their praise for one another seemed sincere. They all pointed out that Qatar has granted the Biden administration’s requests, including assisting with the 2021 withdrawal of U.S. troops from Afghanistan, and remains one of America’s best allies in the Middle East.

Qatari foreign ministry officials claimed their reported support of Hamas and cooperation with the Taliban and the Muslim Brotherhood is offered in part because the U.S. has requested that Qatar host them. They deflected questions about the U.S. designation of Hamas and Hezbollah as terrorist groups, saying that Qatar hosts people, not organizations, and that it coordinates its actions with the U.S. Perhaps the Senate Foreign Relations Committee can ask administration officials about this.

So, how do U.S. officials square our Central Command’s (CENTCOM) first two “command priorities” — that is, to “deter Iran” and to “counter violent extremist organizations” — with having CENTCOM’s base in a country that welcomes some U.S.-designated terrorist organizations and maintains a good relationship with Iran? Qatari officials say the U.S. has asked them to act as a backchannel with Iran — which, if true, is reminiscent of the clandestine talks the Obama administration held with Iran in 2014, when they promised to keep Israel informed about the nuclear negotiations but did not. A former U.S. ambassador to the region confirmed this backchannel request to me.

The reason Qatar invested $1 billion to upgrade the U.S. base in Al Udeid, where CENTCOM is based, is not only to curry favor with the U.S. but also because it acts as a defense against Iran. Deep down, the Qataris understand that Iran’s Shiite leaders do not respect their Wahabi Sunni Islam; it is probably only a matter of time before they collide. To regain some leverage to pull Qatar away from America’s adversaries, we should float the possibility that another U.S. ally in the region might be willing to build us an equivalent air base.

For decades, U.S. administrations of both political parties have mismanaged our relationship with Qatar. As a major general in the Qatari defense department pointed out, his country faces threats from 360 degrees, something that may be difficult for policymakers in Washington to understand. Tribes, clans, culture matter in the Middle East — not simply nationality, which the West prioritizes in its analyses.

This general notes that Iran plays the long game and believes its recent rapprochement with Saudi Arabia may be, in part, a way for the mullahs to gain time. He says Iran is determined to complete a nuclear weapon and to return to the world scene; it also seeks sanctions relief and, most importantly, to ensure the Islamic regime’s survival.

The perception that the U.S. has become weak and unreliable — caused in part by the Afghanistan withdrawal and Trump’s inaction against Iran after its 2019 attack on Saudi oil facilities — is a narrative taking hold in some Middle Eastern nations. American embassies in the region, however, object to this narrative, claiming that everyone knows the U.S. remains a strong force in the region and, when the chips are down, Middle Eastern countries will reach out to America. Yet, when Iran-directed militias from Iraq and Syria have attacked American troops in Syria, we have infrequently responded, casting doubt on America’s resolve.

When speaking to members of Congress over the years, I’ve heard one of two opinions when I bring up Qatar: The first is, “They are a good friend, and even if they are not, our other Arab ‘friends’ can be equally bad.” Or, alternatively, “We are in bed with an enemy.”

Like the Trump and Obama administrations, the Biden administration wants to disengage some entanglements in the Middle East. Our relationship with Qatar may be a means to an end, providing short-term stability. But what if Iran becomes a nuclear state — will its relationship with Qatar undermine America’s national security interests?

We should be exploring this question in Washington, even if we are consumed with the threat of China’s aggression in the Indo-Pacific and Russia’s war in Ukraine.