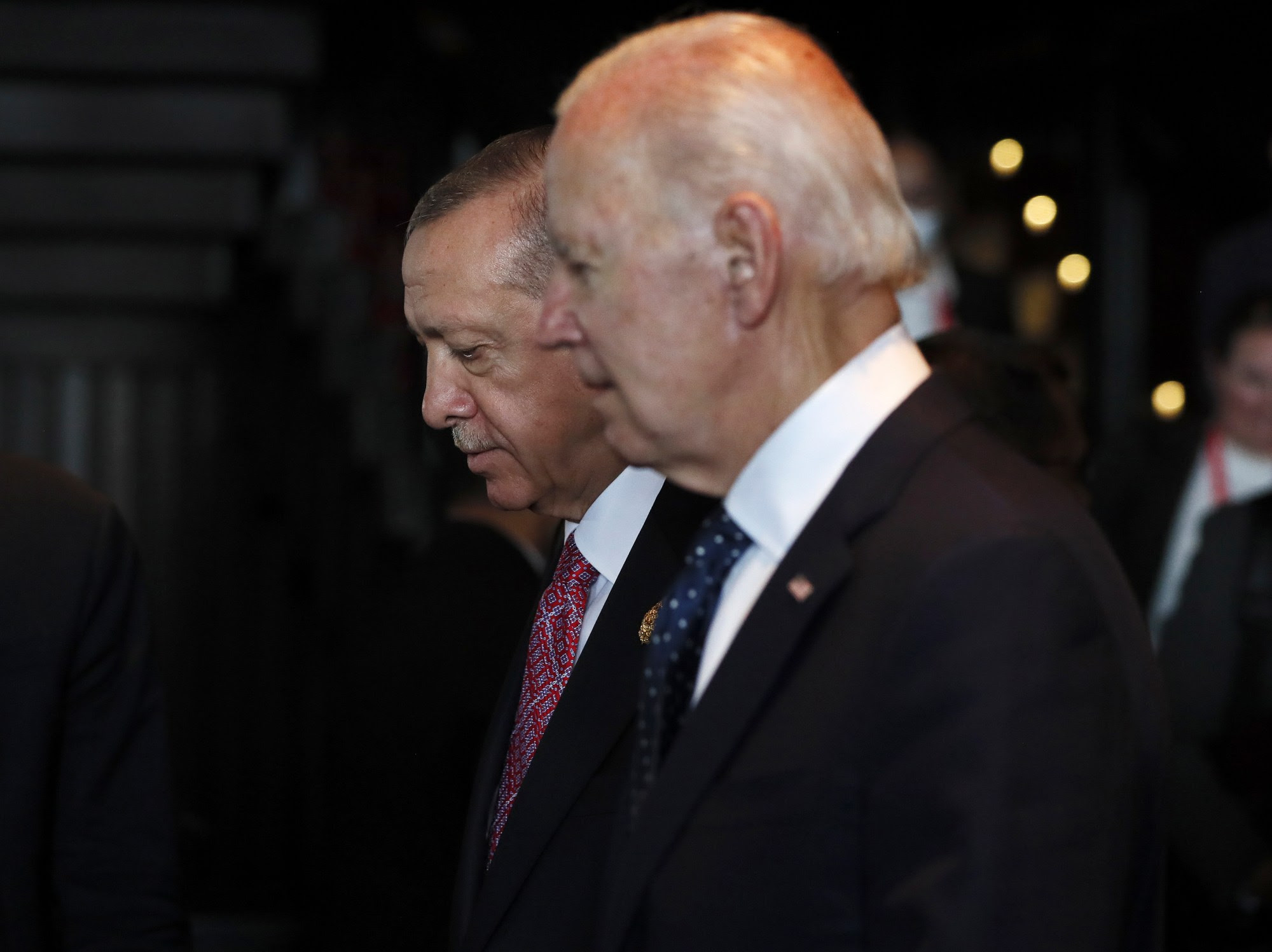

Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, left, walks with U.S. President Joe Biden during the G20 leaders’ summit in Nusa Dua, Bali, Indonesia, Nov. 15, 2022. Biden administration officials are toughening their language toward NATO ally Turkey as they try to talk Turkish President Recep Erdogan out of launching a bloody and destabilizing ground…. Made Nagi/Pool Photo via AP

This article originally appeared in The Hill on August 6, 2020

Over the 20 years since President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan took the mantle of Turkish leadership, the U.S.-Turkey relationship has been challenging. Erdoğan took his nation in a more sectarian Islamist direction, leaving behind Americans’ idealized vision of Turkey as a secular, democratic Muslim nation.

Two challenging periods came when Turkey decided not to allow American forces to operate from Turkey in their Iraq mission, and Erdoğan’s complaint that America was harboring the alleged leader of an attempted 2016 coup, Fethullah Gulen.

Even more perplexing was the defiant Turkish decision to purchase the Russian S-400 anti-missile system, a choice that could compromise NATO defenses. There were Western options to the S-400 available, and the U.S. made it publicly and privately clear that this was unacceptable. Turkey has the second-largest military in NATO and sits in a crucial geographic location between Ukraine, Russia, Iran and the Levant.

The National Defense Authorization Act requires Turkey to give up the S-400 system as a condition for sanctions relief. The presidency of Turkish Defense Industries was also sanctioned under Section 231 of the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) for engaging in significant transactions with Russia’s primary arms export entity.

In addition, in the Halkbank case, the U.S. Department of Justice charged Turkey’s government-owned bank with circumventing U.S. sanctions by facilitating gold payments to Iran. A 7-2 Supreme Court majority has already scrapped Halbank’s initial attempt to invoke sovereign immunity, and the case is still lingering in the lower courts.

Earlier this year, Brian Nelson, undersecretary for terrorism and financial intelligence, warned Turkey that it could lose access to G7 markets if it continues to bypass American sanctions related to Russia. Congress is also displeased that Turkey gives safe haven to the American-designated terrorist organization Hamas, undermining the stability of America’s trusted ally Israel.

Secretary of State Antony Blinken, testifying before Congress, made it clear that the problems in the relationship cannot be swept under the rug. Nor is it sufficient to have a merely transactional relationship with NATO’s second-largest military.

Turkey is not a natural ally of Russia or Iran, but is in close geographic proximity to both. Regarding Iran, Turkey has a historic rivalry that includes 11 wars. They are two major non-Arab Muslim rivals, vying for supremacy in the Islamic world — one Turkish Sunni and the other Persian Shiite. They also support different proxies in the Middle East.

Where they do agree is on suppressing their respective Kurdish minority populations, which they view as seditious.

Turkey is burdened with millions of displaced refugees from the Syrian civil war and the economic and humanitarian catastrophe from the 2023 earthquake. Would Turkey accept permanent Iranian control of much of Syria in exchange for repatriation of refugees to Syria? It would be a mistake, as a permanent Iranian presence would eventually undermine Turkish security. It would also dramatically increase the risk of a regional war, as Israel will not accept a permanent Iranian presence on its northeastern border.

The result would be another refugee exodus from Syria landing on Turkish territory, restarting Turkish problems all over again.

But times may be changing, and potentially for the better, thanks to some recent pragmatic decisions by Turkey — for example, its recent pivot toward controlling inflation the orthodox way, by raising interest rates and strengthening the Turkish currency. This is a tough pill to swallow for Erdoğan, as it may decrease GDP in the short term. However, inflation was already undermining export growth and GDP in a cascading downward spiral, making western investment less likely.

Erdoğan, for years, has wanted Israel to send its natural gas through a new underwater gas pipeline to Turkey and then on to Europe, which would decrease European and Turkish dependency on Russian gas. This would be of economic benefit to both Turkey and Israel.

However, for Israel to make that significant commitment, Turkey must be trusted in a deal that stands to last for decades. Can Israel make that leap? Erdoğan and Netanyahu are scheduled to meet this September.

Wall Street and investors, in part, take their cues from the 2023 State Department Investment Climate report on Turkey. On the positive side, Turkey treats foreign investors the same as Turkish investors, with few restrictions on acquisitions by foreign firms. The U.S. State Department publicly looks favorably on the Turkish economy because of its large domestic market, favorable demographics, skilled workforce, and strategic location.

However, its “opaque rulemaking and legislative processes” add “risks for investors.” But what was most negatively highlighted by the State Department report is the lack of Turkish export controls and sanctions compliance.

The path to a prosperous Turkish future runs toward the First World economies of America and Europe, not toward the Third World economies of Russia and Iran. According to Brookings, Russian investment in Turkey comprised only 3 percent of all foreign direct investment from 2007 to 2015, whereas European direct investment made up a whopping 73 percent. The EU is Turkey’s largest trading partner. Turkish exports to the U.S. also top exports to Russia.

For a productive relationship, America must see Turkey as it views itself, not as we wish it were. As Asli Aydintasbas and Jeremy Shapiro write in Foreign Affairs, Turkey sees itself as a “rising post-Western power taking its rightful place on the global stage. It no longer seeks American approval and wants not to be reliant on the West.” Still, “Turkey does not want to switch sides for security from NATO toward the Shanghai Cooperation Organization with China and Russia.”

As Turkey marches forward, it needs to balance its desire for an independent course in a dangerous region while managing its relationships with its most important security ally, the U.S., and its most important economic partner, the EU, while dealing with an unpredictable sanctioned Russia and Iran, and an economically expansionist China.

To that end, Erdoğan must observe and enforce U.S. restrictions in its dealings with Russia and Iran. A good start would be conduct quiet diplomacy with the Biden administration to replace the S-400 system, and to tell Hamas to find another host. This will go a long way toward repairing the U.S.-Turkish relationship, as the U.S. is sure to meet Erdoğan halfway.